|

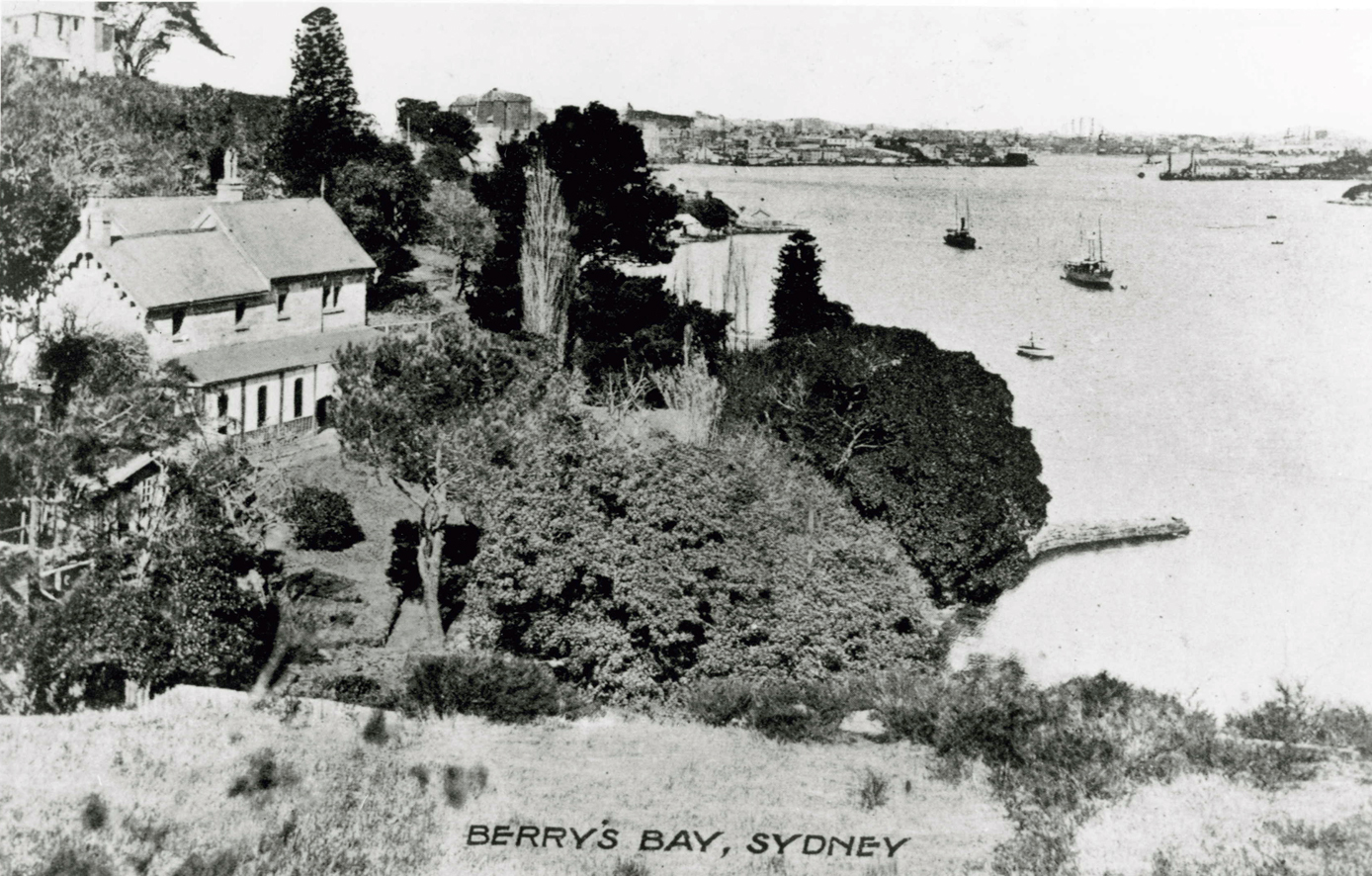

Gothic architectureIt is no coincidence that Gothic architecture began appearing around Sydney Harbour after the arrival of the Scottish-born Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1809.Where the English had embraced classical styles during the Georgian period, the Scots were more inclined to look to their own heritage for inspiration. The ‘Gothick’, as this early 19th century manifestation of the style is called, became very evident in Sydney with the castellated Government House stables built on the rise above Bennelong Point and the fortification that Macquarie built on that point around 1817. Indeed, some thought the function of the so-called Fort Macquarie was more aesthetic than defensive. The shift from classical form to Gothick was advanced in the late 1820s with WC Wentworth’s ‘Vaucluse House’ at the eastern end of the Harbour and the construction of the castle-like Goverment House above Fort Macquarie in the early 1840s. The style was almost universally adopted for ecclesiastical architecture. The English architectural writer JC Loudon published his An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture in 1833, probably the most influential of several pattern books that provided design advice to the wealthy and aspirational. Most of the dwellings depicted were Gothic; characterised by high pitched roofs, asymmetrical configuration and occasionally a castellated tower. Loudon suggested that the ideal location for such a villa was ‘a day’s journey from the metropolis’ and then in a varied landscape with a village nearby for added picturesque appeal. Those books found their way to colonial libraries. A villa in St Leonards was barely an hour away from Sydney by rowing boat and foot, but it was sufficiently separated by the Harbour to accord with Loudon's ideal; and the elevated shores and ridges that rose back from the water afforded wonderful views. By the end of the 1840s, the dispersed settlement was regarded as a village. Many of the first prominent local houses would be Gothic. To the west were ‘Rockleigh Grange’, the home of artist Conrad Martens and ‘Waverton House’, home of Charlotte Carr. ‘Ivycliffe’, the home of Sydney Town Clerk, Charles Woolcott, sat dramatically above Berrys Bay by the 1860s. To the east were ‘Greencliffe’ at Milsons Point, ‘Kirribilli House’ and ‘Sunnyside’ further along and, above Neutral Bay, was ‘Honda’. Of these ‘Kirribilli House’, ‘Sunnyside’ and ‘Honda’ survive. The appeal of the Gothic style clearly spoke of the Britishness of the colonists who chose it for their homes. This national association was consolidated in Britain itself by the work of AWN Pugin and John Ruskin through the 1840s and 1850s. Ruskin, in particular, wrote of Gothic architecture as a form that best reflected the history and characteristics of northern European Christian people. He disparaged the association of classicism with the slavery of ancient times. The Gothic was, by contrast, an expression that reflected individualistic, democratic societies; and expression of ‘enobled labour’ rather than servitude. From this sentiment emerged the English Revival and Arts and Crafts styles. These, too, were popular in North Sydney – testimony to the strength of the local identification with the culture of, what many Australians then still referred to as, ‘home’. |

|